Comics Retailer magazine: A personal history

Prologue: Issues #1-22, produced February 1992-November 1993

by John Jackson Miller

Across 191 issues from 1992 to 2008, Krause Publications' Comics Retailer magazine — which later became known as Comics & Games Retailer, reflecting a change in the readership and the advertising base — traced the ups and downs of the hobby retail market in a way that no other periodical did. It recorded many of the events of the Distributor Wars, and retailers' responses to them. Along with its parent publication Comics Buyer's Guide, it provided a outlet for my early numerical research into comics and graphic novel sales.

Later, it would even become a part of the story of Free Comic Book Day, when in June 2001 Joe Field, owner of Flying Colors Comics in California, would suggest the event to Diamond Comic Distributors in Comics Retailer's pages. The magazine was an important setting for industry conversation, particularly in the days before the World Wide Web.

Across 191 issues from 1992 to 2008, Krause Publications' Comics Retailer magazine — which later became known as Comics & Games Retailer, reflecting a change in the readership and the advertising base — traced the ups and downs of the hobby retail market in a way that no other periodical did. It recorded many of the events of the Distributor Wars, and retailers' responses to them. Along with its parent publication Comics Buyer's Guide, it provided a outlet for my early numerical research into comics and graphic novel sales.

Later, it would even become a part of the story of Free Comic Book Day, when in June 2001 Joe Field, owner of Flying Colors Comics in California, would suggest the event to Diamond Comic Distributors in Comics Retailer's pages. The magazine was an important setting for industry conversation, particularly in the days before the World Wide Web.

The editorships of Comics Retailer broadly break down into three eras: the first two years, described on this page; my tenure as editor, which ran from 1993 until roughly 2003, by which point I was in management and was working more on books, as well as my own freelance comics career; and the later years, edited by James Mishler and Brent Frankenhoff.

My goal in this series of articles is to cover that middle section, while I still (mostly) remember what happened; to cover some of the events of the business as they were being reported on; and to note some of the ways the publication responded to the changing marketplace, touching occasonally on events in my life as they're relevant. (I can't promise the pieces will be monthly, but that seems like a reasonable schedule.)

First, however, let's look at where the business was at the time of the magazine's creation...

The rise of the comic shop

Within 15 years of the modern comic book's introduction in the 1930s, comics had become a mass medium, with sales on a few titles topping 1 million copies per month. Circulation was through a newsstand distribution network selling comics through magazine stands, grocery stores, and drug stores; inefficient (and not a little corrupt), the returnable system required many more copies to be printed than were actually sold to readers. Cheaply priced and poorly printed, comics were a loss leader for those outlets; they had little to no commitment to the medium itself.

The 1950s reversed the industry's fortune through two events. A moral panic in the early part of the decade about comics and juvenile delinquency resulted in Senate hearings in 1954. Designed more to burnish Sen. Estes Kefauver's crime-fighting credentials for a future failed presidential run (he'd become the VP nominee instead in 1956, losing there, too), the hearings' greater effect was in nudging many publishers and resellers away from comics. They were easy to move because of the other factor in the 1950s: television. After the Federal Communications Commission lifted its freeze on new stations in 1952, affilates sprang up, disrupting existing entertainment options everywhere.

With comics no longer the nation's babysitter, sales outlets devoted less space to them. Fighting the tide of declining sales in the 1960s was the super-hero genre, thanks to the creative wave known as the Silver Age — but that came with a cost, as romance, western, and kids' comics began to drop away, making comics more of a niche medium. By the 1970s, comic books no longer functioned as loss leaders, their cover prices having quickly (and painfully) caught up with inflation — and the old mom-and-pop drug and convenience stores carrying comics were giving way to national chains that saw no need for comics.

To the rescue: the comics fans themselves. Phil Seuling and his Sea Gate Distributors in 1973 arranged to buy comics directly from publishers, for sale non-returnably to individual retailers. With comics now being sold by people who actually cared about them and understood the product, the "Direct Market" grew, with other distributors entering the game — which begat more store openings.

To the rescue: the comics fans themselves. Phil Seuling and his Sea Gate Distributors in 1973 arranged to buy comics directly from publishers, for sale non-returnably to individual retailers. With comics now being sold by people who actually cared about them and understood the product, the "Direct Market" grew, with other distributors entering the game — which begat more store openings.

Publishers, liking the guaranteed sales and lower price resistance of comics-shop customers, first tested the waters with titles like Dazzler #1 — and when those succeeded, dove in aggressively. The 1980s saw the Direct Market claiming most of the newsstands' former business.

It wasn't a linear path; there were fits and starts, often because the ease with which publishers could release new titles through the system made gluts of new titles a frequent occurrence. One of the first mini-shakeouts happened in "Black September" in 1983: the major publishers had offered so much to the Direct Market that retailers cut back all at once. By the mid-1980s, it was the turn of the burgeoning small-press publishers, who led to an explosion and glut of black-and-white comics. Along the way, direct market distributors rose, fell, and consolidated.

It wasn't a linear path; there were fits and starts, often because the ease with which publishers could release new titles through the system made gluts of new titles a frequent occurrence. One of the first mini-shakeouts happened in "Black September" in 1983: the major publishers had offered so much to the Direct Market that retailers cut back all at once. By the mid-1980s, it was the turn of the burgeoning small-press publishers, who led to an explosion and glut of black-and-white comics. Along the way, direct market distributors rose, fell, and consolidated.

By the end of the decade, however, another boom was on. 1989's wildly successful Batman movie release boosted interest in the comics to the point that when a new series, Legends of the Dark Knight, was announced, retailers ordered hugely on the first issue. So many copies, in fact, that DC — knowing it could not deliver them all in the same week and fearful that retailers would be stuck with them — took the step of offering a different pastel-colored cover for each week's copies. The variant cover was thus born out of concern for retailers; but it would end up further commoditizing comics, as in the years that followed, Wizard magazine-reading collectors sought to locate versions that were thought rare.

The late 1980s had also brought on a wave of new talents including Todd McFarlane, whose popularity merged with the variant-cover phenomenon in 1990 to produce Spider-Man #1, one of the bestselling comics in years and a book whose gimmick was a polybag around the issue. (Removing it supposedly destroyed its collectible value.) Another major talent, Jim Lee, drew for a new X-Men series whose first issue, across its five covers, would become the bestselling comic book in history with 8,186,500 copies sold to retailers. McFarlane, Lee, and other creators would decamp for self-publishing in 1992, forming Image, an instant goliath in the Direct Market and setting in motion a decade's worth of industry disruptions.

The late 1980s had also brought on a wave of new talents including Todd McFarlane, whose popularity merged with the variant-cover phenomenon in 1990 to produce Spider-Man #1, one of the bestselling comics in years and a book whose gimmick was a polybag around the issue. (Removing it supposedly destroyed its collectible value.) Another major talent, Jim Lee, drew for a new X-Men series whose first issue, across its five covers, would become the bestselling comic book in history with 8,186,500 copies sold to retailers. McFarlane, Lee, and other creators would decamp for self-publishing in 1992, forming Image, an instant goliath in the Direct Market and setting in motion a decade's worth of industry disruptions.

And all along, there were the Direct Market distributors, increasing in number as smaller regional outfits arose to vie against Diamond Comic Distributors and Capital City Distribution. Those two largest outlets had opened warehouses across the continent, running their own trucking fleets to try to attract comics shops to use their services. So many competing distributors meant that existing retailers were encouraged to turn comics shops into chains, while collectors and current retail employees were urged to open shops of their own. A credit bubble developed as the number of distributors multiplied, with retailers offered ever-easier terms to get into the business. Comics stores opened across the street from one another in some cities; my hometown of Memphis saw two cases of cross-street rivals, in addition to other peculiarities, like a large location above a liquor store and a "shop" in what would have been a psychiatrist's office space in a medical center.

An additional and influential factor was the collapse of a tangential hobby, sportscard collecting; many sportscard stores were urged to get into comics, and many sportscard gimmicks, like foil-stamping, made their way into publishing.

An additional and influential factor was the collapse of a tangential hobby, sportscard collecting; many sportscard stores were urged to get into comics, and many sportscard gimmicks, like foil-stamping, made their way into publishing.

So the result in 1992 was a lot of shops ordering comics. There's disagreement as to how many comics shops there actually were. Some have suggested there were between 6,000 and 7,000, with the often-mentioned 11,000 number referring rather to the number of individual retailer accounts, padded by retailers who had multiple accounts — and people who were not retailers at all, but were ordering from the distributors because they were weekend warriors or had otherwise made the case that they should have accounts. (Several publishing offices had accounts of their own, to provide their staffs with the comics they needed to function; none of those arrangements survived into the Diamond Exclusive Era.)

However many shops there were, it was a sizable market: retail customers, and distributors and publishers trying to sell to them. The most serious previous attempt at a retailer magazine, Dave Olbrich's Comics Business, had ended after five issues in 1987-88, colliding with the collapse of the black-and-white comics market; by 1992, the market had many more players and much more money. If it was ever going to work, this would be the time.

From startup to first issue

Comics Buyer's Guide, the weekly newspaper started in 1971 by Alan Light and edited since 1983 for Krause Publications by Don and Maggie Thompson, had long been a force in the business. (Read more about it in my history). By 1992, issues had grown vast from advertising; having shifted to a folded, stapled tabloid, the newspaper could no longer do multiple sections without a polybag.

Comics Buyer's Guide, the weekly newspaper started in 1971 by Alan Light and edited since 1983 for Krause Publications by Don and Maggie Thompson, had long been a force in the business. (Read more about it in my history). By 1992, issues had grown vast from advertising; having shifted to a folded, stapled tabloid, the newspaper could no longer do multiple sections without a polybag.

That meant that issues bulged — particularly when the warring distributors advertised their retailer trade shows. Large sections of the newspaper had been given over to them, content that went over the heads of the majority of readers who weren't, themselves, eligible to attend the events. With so many comics shops starting up, Krause executives saw an opportunity to break off some of that material into a business-to-business magazine.

The idea had been around, as noted earlier: Publisher Greg Loescher said that Marvel's Carol Kalish had started talk of the need for a retailer mag a few years earlier. "Since we (Krause/CBG) were not a comic-book publisher nor a distributor, it made sense for us to publish it as it would be more impartial. Marvel paid for the first cover, thus showing their early support."

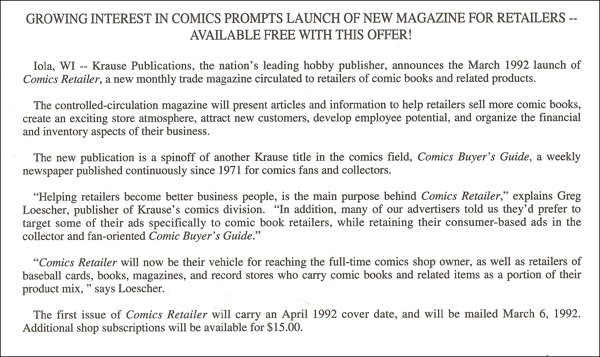

That's right: the lower right-hand portion of the cover was a paid advertisement, much as was the case for Editor and Publisher and other trade magazines. The hobby retail example from which most inspiration was drawn, according to Loescher, was Model Retailer, the magazine for model railroad stores by Kalmbach Publications; like it, Comics Retailer would be free to its readers, most of whom ran comics shops. From the announcement brochure, depicted above right:

And unlike the distributors' catalogs, which only went to their customers, Comics Retailer would be a place to reach everyone at once. Considerable resources went into obtaining and then mining a national Yellow Pages database, giving the publication a circulation in the thousands right from the start.

Postal regulations meant the magazine couldn't just be dropped in the mail; readers had to request it, so contacts by phone or mail had to be made. They were. Other publishing and distribution professionals were also eligible to receive it, as noted in the Q&A section of the introductory flier, at right.

Postal regulations meant the magazine couldn't just be dropped in the mail; readers had to request it, so contacts by phone or mail had to be made. They were. Other publishing and distribution professionals were also eligible to receive it, as noted in the Q&A section of the introductory flier, at right.

As with Model Retailer and many other business-to-business publications of the era, Comics Retailer would also include a bounceback or "reader service" card, where retailers would circle a number in an advertiser's ad to get more information. (It'd later share space with the "Market Beat" retailer sales survey card.)

The first issue of Comics Retailer was produced in February; it went to press usually the fourth Tuesday of the month, for mailing to retailers early in the next month. The debut issue was cover dated April 1992; there was always a one-month gap between mailing and cover date.

KC Carlson, formerly of Capital City Distribution, Westfield Comics, and DC, was hired as the first editor for the magazine; his first column was about life in rural Wisconsin, and how he'd been "mugged" by a herd of deer. (I would later understand that experience myself.) Carlson's first column went on to note that while the magazine would have many things, sales charts and publisher market share charts wouldn't be among them. "The fine folks at Diamond and Capital City do a pretty good job at this, and we felt it would be redundant." What the publication was interested in, he wrote, was charting retailer sell-through, and Carlson solicited ideas for tracking it.

The first issue focused heavily on publisher and distributor news and retailer co-op information; the magazine was the one place where retailers could read about what was going on with all distributors under one cover. Publisher and distributor advertisements were many, as well as ads from fixture manufacturers. A letter column, Dialog, existed from the first issue, featuring letters solicited in advance. Retailers had quite a lot to talk about: the "No holograms!" line on the cover clearly places it amid the gimmick-ridden early 1990s.

Also there from the beginning were columnists. The first outside column in the first issue was by business consultant Harry Friedman; his was a syndicated series, with columns from his catalog being tweaked to refer to comics shops. San Francisco retailer Brian Hibbs was also in the first issue with a piece about back-issue pricing, "Ethics in the Comics Industry," that had previously run in CBG. He'd be in the next issue with his regular column, Tilting at Windmills — a feature that would become the most-read column in the magazine for years, save for the later Market Beat sales reports.

Bob Gray, a comics retailer in Syracuse, N.Y., also had a reprinted CBG contribution in the first issue on computerizing one's store — and Gray also contributed the first of his Maintain the Momentum columns, the debut talking about professionalism in the business.

Bruce Costa, a comics-shop owner turned retailer liaison for Marvel (and later Heroes World Distribution employee), contributed his first Suggested for Mature Retailers column for Comics Buyer's Guide #923 back in August of 1991; he brought the column over to Comics Retailer with his first one for the magazine about keeping a clean store: the column's teaser on the front cover, "Would you let your Mom in your store's bathroom?" raised eyebrows.

Bruce Costa, a comics-shop owner turned retailer liaison for Marvel (and later Heroes World Distribution employee), contributed his first Suggested for Mature Retailers column for Comics Buyer's Guide #923 back in August of 1991; he brought the column over to Comics Retailer with his first one for the magazine about keeping a clean store: the column's teaser on the front cover, "Would you let your Mom in your store's bathroom?" raised eyebrows.

Product-specific columns were also part of the initial package. Game designer Scott Haring's column, From the Game Shelf, also was there from the first issue; it would run off and on for many years. There, too, was Steve Fritz's column about trading-card retailing, Wild Cards, one of several columns that would later cover the subject. And publisher Loescher wrote the first magazine-closing Punchline column. Many of the features would recur monthly or nearly monthly over the years, with Hibbs, Gray, and Costa forming the core comics commentariat, along with later arrival Preston Sweet, a retailer from Athens, Ga., whose Small Store Strategy column focused on shops with a limited footprint.

So, much of the core was in place from the start, except for the sales reporting – and Sweet, who started in the seventh issue. Carlson, however, didn't remain in place long, hired back to DC's staff after just four issues. Don Butler, from Krause's sports magazines, stepped in with the sixth issue, cover-dated Sept. 1992. He served through the monumental "Death of Superman" event in November 1992, and the character's subsequent rebirth (see my video discussion of the phenomenon) in April 1993 — the moment at which the market had peaked. Nobody knew that at the time, although danger signs were appearing: conversation in the magazine in later 1993 issues focused on late shipping of titles by Image; it, and some other publishers, had grown too quickly during the boom market.

Butler edited until the 20th issue (dated November 1993) when he, too, departed. Sendai Publications, which had momentarily found a hit in Wizard rival Hero Illustrated, announced plans to launch its own retail trade magazine, Comic Book Business — and hired him away. That publication wouldn't last long, and neither would Wizard's Entertainment Retailing, also launched to compete with Comics Retailer; in later years I would later hire Butler to rejoin the comics staff.

But at the time it meant a third potential competitor in the suddenly crowded space, and added stress to the Krause comics staff at a time when Don Thompson was recovering from illness — yet still turning in long days dealing with record-sized issues of CBG.

"Not another editor to break in?"

Here, I entered the picture. I had been a comics reader since age six. Where other kids' parents threw their comics away, my mother was a grade-school librarian; she encouraged me to protect my comics and put them in order.

As such, I'd kept my comics in good, orderly condition into my teen years, when I indexed my collection and started my own local fanzine. (At right, the self-drawn logo from my first column about comics, with the not-Howard duck reporter in place of yours truly, who literally typed on a Smith-Corona in a closet full of comics. I was a better writer than an artist!)

As such, I'd kept my comics in good, orderly condition into my teen years, when I indexed my collection and started my own local fanzine. (At right, the self-drawn logo from my first column about comics, with the not-Howard duck reporter in place of yours truly, who literally typed on a Smith-Corona in a closet full of comics. I was a better writer than an artist!)

I discovered Comics Buyer's Guide around this time, and found through its classified ads the existence of a small press network of fans circulating minicomics. I contributed to that community some over the years through high school and college, where I edited my high school and then my college newspaper. After a brief side trip to pick up a master's degree in Soviet Studies (the USSR collapsed on my dissertation, discouraging me from going further) I took a job in my hometown of Memphis editing a line of trade magazines for the lumber industry.

My interest in lumber barely keeping me awake through the day, I was again served by an ad in Comics Buyer's Guide: this one, from the publisher itself, advertising for a replacement for Butler. I flew up to Wisconsin for an interview on Nov. 1, 1993 (I recall River Phoenix's death was announced on the hotel clock radio that morning); visited the headquarters in rural Iola, spoke with Loescher, and took a lunch meeting with Don and Maggie, long idols of mine.

My ability to put together a magazine on short notice supplemented by nine years of having read the Thompsons' coverage of the market, I was hired the next day. Three weeks later, I moved 800 miles to Wisconsin — my comics collection to follow when the truck arrived.

Starting the same week was Jim Owens, a former Diamond field representative hired to serve as one of the magazine's ad reps; our efforts on the magazine would dictate the course of publication for the next several years, helping it to prosper when much of the rest of the comics business was suffering. Owens, in particular, saw the promise that Magic: The Gathering held as a product that would keep many stores — and the publication — alive.

But that was in the future. Just before Thanksgiving — and 25 years to the day before the publication of this piece — I went to work. Over in the production department, the 22nd issue of Comics Retailer (at left, cover-dated January 1994) went to press that day; I familiarized myself with it and began contacting columnists.

But that was in the future. Just before Thanksgiving — and 25 years to the day before the publication of this piece — I went to work. Over in the production department, the 22nd issue of Comics Retailer (at left, cover-dated January 1994) went to press that day; I familiarized myself with it and began contacting columnists.

"Not another editor to break in?"

remarked one of them (either Hibbs or Sweet) in our first conversation. A fair thing to ask, given the turnover the magazine had seen. I expressed confidence about having been thrown into the deep end — not having the slightest idea just how deep that was.

It was late 1993, and the comics industry's bottom was about to fall out. I had moved from studying one falling empire to another.

Next month: Starting the new era off right — with an industry collapse!